2013 is, understandably given the cinema release of The Great Gatsby, the year of the Zelda Fitzgerald novel. Zelda has always had a voice – she wrote novels, memoirs and copious letters – but writers seem hell-bent on giving her a newer one.

This current trend for reassessment is especially interesting in light of Zelda’s mental health. Therese Anne Fowler‘s Zelda doesn’t have a defined mental illness until 50 pages before the end of this 350+ page novel, which covers the entirety of Zelda’s and F. Scott Fitzgerald’s relationship, from their first meeting in 1918 until Scott’s death in December 1940.

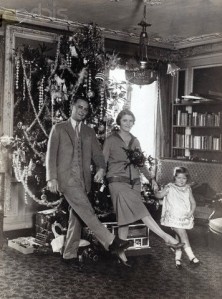

In the ‘Team Scott’ vs. ‘Team Zelda’ fight that Fowler references in her end notes, Fowler has plumped firmly for Team Zelda. At home in Alabama young Zelda is feisty, smart and talented, awed by the decadent Manhattan life that she embarks upon when she marries Scott. Zelda leaps into it though, partying hard, hanging out with fashionable cultural figures and, over the next 15 years, moving with Scott to California, Paris, the French Riviera and Italy, befriending Cole Porter, Picasso and, importantly for the novel, Ernest Hemingway.

Hemingway and Scott were close, but Hemingway and Zelda had an antagonistic relationship – no spoilers here, so I’ll just say that Fowler explains it by portraying Hemingway as a total shit – and at one stage in the novel she blames him for her life becoming a disaster.

The line: “Ernest Hemingway is to blame” is one of many portentous sentences that Fowler gives Zelda. In an imagined memoir, it’s an easy (and sometimes clumsy) trick to let the reader know things are not going to go well. Most people reading this book will already know that the Fitzgeralds’ lives slid, and turned into a tragedy that Fowler’s light, frothy tone doesn’t completely capture. Having said that though, Zelda’s reaction to Scott’s death is genuinely moving; Fowler’s Zelda is a sympathetic victim of her controlling, obsessive husband and her own escalating mental illness.

Was she a victim though? The reams of letters and contemporary writings about the Fitzgeralds suggest they destroyed each other, rather than one being entirely to blame. (The letters also show a passionate, more loving relationship than the one in Z). The scholar Sarah Churchwell wrote a review of Z in The New Statesman in which she pointed out that the real Zelda was a lot less boring and sanctimonious than Fowler’s creation. Certainly it’s well-known that, rather than being reluctant to take her clothes off in public, Zelda was all for it; that she was a happy lush rather than a prim drinker; and that she wanted her daughter Scottie to be ‘beautiful and a fool’ and was not as admirably maternal as Fowler paints her. Fowler’s Zelda is a bit bland in comparison to the real one, and the lines Fowler gives her are often banal. Zelda’s actual use of language in her writings was far richer.

As for Zelda’s mental health, she finally falls apart because she’s pushing her body too hard through ballet. Her doctors tell her that her ambitions (dance, writing, art) have caused her to become ill, and she should stop trying to ‘compete’ with her husband – a fairly accurate portrayal of attitudes towards female mental health in the 1930s. In the novel Scott is callous, which is at odds with the Scott who wrote to Zelda’s doctor in 1934.

As for Zelda’s mental health, she finally falls apart because she’s pushing her body too hard through ballet. Her doctors tell her that her ambitions (dance, writing, art) have caused her to become ill, and she should stop trying to ‘compete’ with her husband – a fairly accurate portrayal of attitudes towards female mental health in the 1930s. In the novel Scott is callous, which is at odds with the Scott who wrote to Zelda’s doctor in 1934.

Fowler’s end note says that Zelda was probably not schizophrenic, but would now have been given a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. Unfortunately the Zelda she gives us doesn’t convince, and this otherwise entertaining novel, with its colourful period flavour, is weakened by the heroine Fowler is fighting so hard for.