Twelve pages in, and Wendy Wallace has made me feel panicky. Anna Palmer, spirited heroine of The Painted Bridge, has just been locked in her tiny room at Lake House asylum, and the description – ‘...anger gave way to fear, to a feeling that she was drowning, that something fluid and dark was rising inside and choking the breath out of her…‘ – is so perfectly judged that instant claustrophobia ensues.

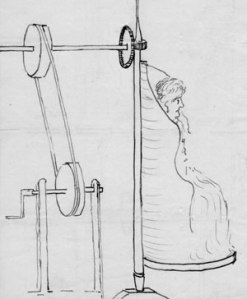

Early in the novel (no spoilers – if you want to know what happens you can buy the book here) we find out that Anna is at Lake House because her husband Vincent thinks she has acted irrationally in going to help the survivors of an accident at sea. Anna has no mental illness, but she is ultimately treated for ‘mania’. Wallace’s lyrical language gives a false sense of security on occasion, lulling you into thinking that hey, maybe living in a Victorian asylum wouldn’t be too bad, and then she writes about the spinning chair.

‘Anna was sitting in her own urine. She was sick, suddenly and violently, down the front of her dress…. The chair began to move again, in the other direction.’

I was fortunate enough to have a good chat with Wendy Wallace about Victorian mental health at an event in March, and her knowledge of the subject is immense. She ‘did masses of research’ for this impressive début and, like the best historical fiction, the story wears her knowledge lightly. There is nothing crowbarred in to show off, and everything is integral to the development of character and/or plot; judging by the amount of historical novelists who insist on telling their readers every single thing they’ve learned, knowing what to leave out is not an easy skill to master.

Wallace based the loveable Lucas St Clair on Dr Hugh Diamond, who believed photography could help in the diagnosis of mental illness, and she tried Victorian photographic techniques to get this vital sub-plot just right. She read people’s experiences of the spinning chair in the Wellcome Archive and familiarised herself with other tortures: the use of leeches, and freezing showers like the one that nearly kills Anna. All painfully true. Case notes from the Greater Glasgow Health Board archives show that in 1820 the ‘whirling chair’ was used to treat a woman who ‘refused to amuse herself in any way’; after an hour of the horror she still refused to sew, apparently. This treatment was meant to sort of jumble up the brain to shake it back into sanity, whereas the practices of cold showers and shaving inmates’ heads were designed to cool down ‘overheated brains’.

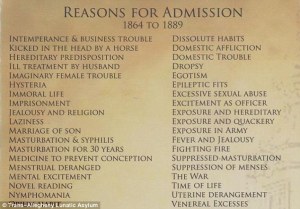

Though it seems absurd to think that husbands could do away with their unwelcome wives, daughters and mothers on a whim, Sarah Wise’s Inconvenient People (see earlier post) proves it happened so regularly that Anna’s experience, rather than being far-fetched, is actually almost par for the course. A list of reasons for admitting inmates to a 19th century asylum in West Virginia shows how ludicrous the system was – though, interestingly, mania isn’t actually listed – and it was in the best interests of asylum proprietors to keep financially lucrative inmates like Anna locked up for as long as possible.

Wallace has created a fascinating cast of (primarily female) characters for The Painted Bridge, all of whom are three-dimensional and complete with desires, fears and dark sides that make them relatable today. Creating characters whom a modern readership can understand is an enduring challenge for historical novelists, and Wallace has risen to it beautifully. Anna is one of the most endearing heroines in recent reading memory, and her battles against the real-life demons of Victorian mental health ‘care’ make for a hugely satisfying read.

You can read a Wendy Wallace article about women in Victorian asylums here.